The Problem of Writing for Others

On Cyrano de Bergerac, Leo Strauss / Plato on Sophistry, and Anonymity

In an earlier post, we considered the difference between reading and thinking; as it turns out, reading, despite what we might expect, can be deleterious to thinking if not undertaken properly. Here we will consider why writing for others is almost necessarily bound to be an obstacle to thinking clearly. This runs against our expectation, since you—like me—probably find that new ideas emerge in the process of writing; that there is often a feeling of discovery while writing and a clarification of thoughts that were previously hazy or insufficiently distinct.

We can see the problem through the following comparison: imagine an art critic like those presented in Tom Wolfe’s The Painted Word. Rather than observing or contemplating the beauty of an art piece, they have begun to look at art as an object within a social nexus that, if presented properly, can bring the critic greater social status and prestige.

When we write it is difficult not to think of how it will be received. Many who write hope that their words will cause the world to change; they feel important as they extol some kind of vision for how the world ought to be. And precisely because they have taken on this important burden they almost cannot help but be delighted when they encounter readers who praise them.

Now, I think our natural inclination to this is to say: DUH!

So one last way to put the problem in my own words before I turn to the words of superior men is to say this: on one hand we assume that we are the sort of person who can easily manage the pressures that the desire for social status, prestige, honor might impose on our mind’s ability to access the truth. We think that we can still (through the protection of anonymity) state the truth frankly and without regard for pleasing our audience.

AND YET, on the other hand, when we look around, don’t we see countless examples online and elsewhere of people who lose their edge or who sell out or who backstab people who helped them climb the ladder or who are hacks who know how to manipulate a certain type of audience? So most people don’t manage this problem as well as they think. That means we have to be cautious.

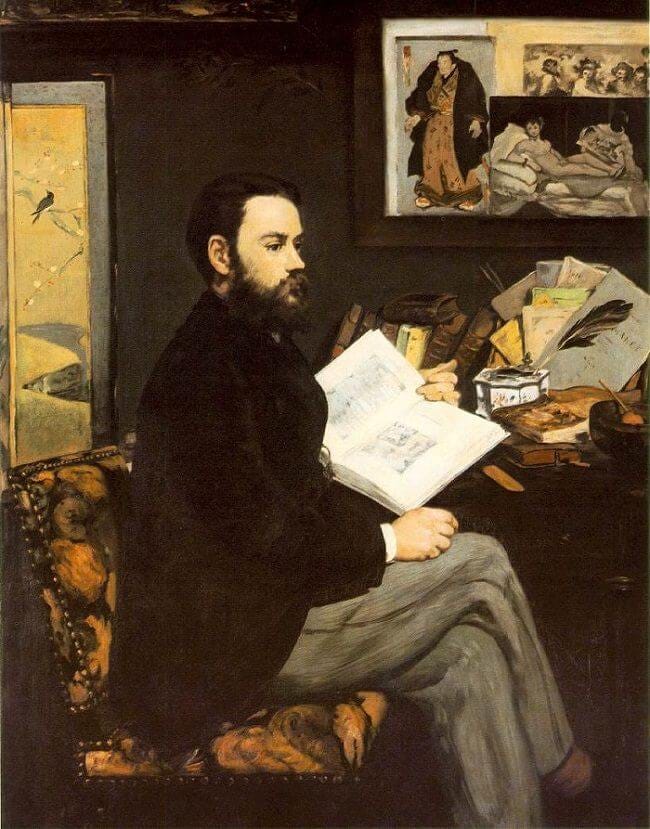

In order to illustrate how writing for others poses an obstacle to us understanding the truth, we will turn to three core examples: Edmond Rostand’s play Cyrano de Bergerac, Leo Strauss’ account of the sophist in Natural Right and History / a few quotations from Plato that confirm his account, and anonymous twitter writers and how much or to what extent they can get beyond the problems posed by Cyrano and Strauss when they write.

I. Edmond Rostand’s Cyrano de Bergerac and the Problem of Writing

The play was written by a talented Frenchman in 1897 and was set in Paris in 1640. Its titular character is a spiritual aristocrat of the highest type who is at once a peerless warrior and an inimitable poet. Throughout the play he illuminates what it means to be noble for the reader; where lesser men perceive dangers that make them say, “I can’t go there,” Cyrano perceives a choice and an opportunity. Fear of death makes weak men say that they are compelled; Cyrano laughs at this alleged compulsion and seeks to make his life into a beautiful work of art that has contempt for such fear.

But we aren’t here to interpret the play as a whole; rather we turn now to his remarkable account of why writing for others is a great problem that threatens to distort our thinking.

In Act Two of the play, one of Cyrano’s rivals, Count De Guiche, admits that he has been impressed by Cyrano. Indeed, he has been so impressed that he gives Cyrano the opportunity of a lifetime: patronage so that Cyrano has the leisure to read, think, and write. Cyrano is greatly tempted by this prospect; he has a five act play called “Agrippina” that is already completed and he would have a chance to stage it.

There is one string attached that De Guiche sees as enhancing the opportunity, but that Cyrano sees as a death knell for the opportunity; namely, Cyrano can have his plays / poems “corrected” by Cardinal Richelieu. As many of you know, the historical Richelieu was at the heart of French religious, political, and cultural life for about 30 years. To have one’s poems connected to Richelieu would guarantee an audience that is both large and highly influential. Cyrano is invited to join the elite of the elite in what we might call his day’s establishment.

Cyrano’s response to the idea that Richelieu would “correct [his] flaws”…?

“Impossible! My blood would turn to ice before I’d take a single comma out.”

Cyrano says much more; but, this statement alone suffices to indicate that Cyrano understands himself as someone who has mastered his craft and who writes with logographic necessity: each word and piece of punctuation is exactly where it needs to be in order to transmit the truth to the reader who carefully attends to such things. Imagine telling Plato and Nietzsche to correct the flaws in their writing!—Perhaps Cyrano couldn’t hope to hit their heights, but he refuses to acknowledge the conventional contemporary elite as a standard for his work. He aims for eternity and can therefore accept no smaller souled man as his judge.

Cyrano’s friends are astonished and admonish Cyrano for being stubborn and foolish. Cyrano replies with a beautiful speech that powerfully expresses the resplendent nobility of his soul; it is too long to quote in full so I’ll bring out its most salient features.

Cyrano perceives that if he has to write with any strings attached, he will not be able to say true things. He fears that his thinking will be subtly conditioned by the love of honor; that outwardly bending the knee once—even while internally refusing to bow—prepares the way for losing one’s interior freedom. Cyrano wishes to be maximally free and a life devoted to winning honor and recognition from others would make him, in a crucial respect, the slave of others.

Is Cyrano foolish for not taking this opportunity? Is there a way to salvage it?

We might be tempted to think something like: well, maybe I’ll have to please the patron a few times, but eventually I will get to write what I want!—but how many journalists or academics have thought something like to that themselves?—and how are journalism and academia doing with respect to truth telling?

Honor loving is a powerful passion; as Cyrano suggests, it is very tempting to want to see one’s work praised in the highest newspaper or to hear others use phrases that one coins. But one can easily become obsessed with seeing oneself through the eyes of others and forget to “start on that long planned voyage to the moon,” as Cyrano says.

Cyrano is a warrior and poet; just as he is too physically strong to fall under the power of a lesser man so too does he carefully attend to his interior freedom.

II. Leo Strauss and Plato on Sophistry

Leo Strauss’ book, Natural Right and History, is a dense and rewarding account of the obstacles that stand between us and the recovery of the thought of the classical political philosophers. Strauss shows the depth of the difficulty of recovering classical thought as it understands itself, then attempts to show us what we might hope to recover, and then turns to how the classical teaching was wittingly or unwittingly lost or rejected.

However that may be, we return to our theme through Strauss’ account of the Sophist in Chapter 3: The Origin of the Idea of Natural Right.

The word “sophist” can mean many things but through Plato’s presentation of the sophists, it has come down us as a man who teaches noble subjects for pay. A sophist is different from an erring or mistaken philosopher, because he is driven, at bottom, by a fundamentally different motivation. Indeed, a sophist might very well teach true things on a regular basis.

Here, Strauss powerfully brings to light the essence of a sophist and what motivation moves his soul:

“The sophist, in contradistinction to the philosopher, is not set in motion and kept in motion by the sting of the awareness of the fundamental difference between conviction or belief and genuine insight. But this is clearly too general, for unconcern with the truth about the whole is not a preserve of the sophist. The sophist is a man who is unconcerned with the truth, or does not love wisdom, although he knows better than most other men that wisdom or science is the highest excellence of man. Being aware of the unique character of wisdom, he knows that the honor deriving from wisdom is the highest honor. He is concerned with wisdom, not for its own sake, not because he hates the lie in the soul more than anything else, but for the sake of the honor or the prestige that attends wisdom.” (pg 116)

The philosopher is principally moved by the desire for knowledge for its own sake. He wishes to understand the truth about the whole; this is not practical knowledge. The sophist is aware that wisdom is what is most excellent in man, but he can’t help but be drawn by the concern for others recognizing that he is wise and so honoring for him for his wisdom. Whatever wisdom he acquires is acquired for the sake of honors being conferred on him which are of a practical benefit. He has confirmation of his worth through the eyes of others that he is better than most men. The difference between him and the philosopher is that it is this confirmation of his worth that makes the sophist’s life worth living.

The sophist, though, finds himself in an uncomfortable position. For, if or to the extent that he knows the truth, it will probably conflict with the commonly accepted or conventional account held by the many. And so he will have to either conceal his wisdom or propagate the conventional view, albeit with a superior articulation to that of the many. In this way, he can’t be honored for his wisdom, but only for flattering the many.

In Plato’s Apology of Socrates, when Socrates discusses the sophists he says that they hope to gain from their youthful students, “money and [for them to] acknowledge gratitude besides.” (20a; translation by Thomas West) Which is to say, the sophists really care that their students recognize the benefaction that they have been given. Of course that is an understandable motivation or wish, but it is not a philosophic wish in the strict sense.

The sophist, then, is a lover of honor. There are much lower and worse ways to live. But the sophist is contemptible because he seems to grasp more clearly than most what the best way of is, and yet he settles for something less.

III. Conclusion: Is Anonymity a Way Out of the Problem?

No.

In a time where people lose their jobs for holding opinions that would and should be held as normal in almost every previous point of human history, anonymity is a great blessing for truth tellers. Socrates died for telling the truth (though he certainly took his own steps to protect himself so that he could live until the age at which he felt he was suffering cognitive decline). Anonymity helps protect writers from political persecution. But it does not protect them from the problem of loving honor more than the truth in their soul.

Consider this tweet:

Even when the amount of real honor or prestige is very low (the highest hope being a substack that pays the bills) many anonymous users (and others) find themselves losing their minds over petty indignities and insults.

There is no clear process for liberating oneself from the love of honor or recognition from others. Rigorously examining oneself and testing one’s ideas for coherence through conversation with intelligent friends is the only pathway I can see for managing this permanent problem.

Thanks for the insightful article. It can be difficult to strike the right balance, but merely being mindful of the problem helps. And, yes - perhaps the only venue that offers lower stakes than RW Twitter is the Academy, itself! 😂 Yet, here we are!