The ancient Greek word that refers to poetry is poesis which also means to do or to make. If great writers make or create entire worlds with their words, our task as readers, then, is to attempt to re-create those worlds for ourselves. Another way to think about our task, is to think of ourselves as explorers who carefully chart out undiscovered terrain or fall further in love with a charming and familiar countryside.

In order to open ourselves to learning from the books, we have to—to the extent possible—temporarily set aside our own notions of what is good and bad, or just and unjust. Setting these thoughts aside allows us to sympathetically try to understand the arguments in a book or the motivations of the characters as they understand themselves.

Let me offer an example of what I mean. When we turn to Beowulf, we will see peoples who are ruled by warrior kings. We might not be especially interested in returning to the rule of warrior kings (though some are!), but we do want to understand why the Danes in that story thought this way was best. By reading sympathetically, we do not say that we agree with everything a philosopher, poet, or novelist presents, but we can say that we understand them. In this way, we are trying our best not to project our own understanding of the way things are onto the book, but, rather, we are trying discover the thoughts of someone else in the world that they have made for us.

In addition, by reading sympathetically, we might also discover that while the Puritan colonists of the 1600s had very different customs than we do today, it is possible to see that there are still fundamental similarities. Customs, or the ways that peoples have decided to do things, might be understood as various attempts by human beings to solve or manage certain problems. There are many ways to approach these problems, but, there are problems that are intrinsic to human life as such. In other words, while justice, love, and other fundamental concerns are understood differently in different times and places, aren’t those fundamental concerns at least felt in all times in places? Every time we open a great book we have a chance to test out this hypothesis, by attempting to give an articulation of the deepest concerns of the human soul or mind that we find in each work and then see if those concerns still remain our own.

We ought to read sympathetically, but we should also read carefully. Plato talks about writing in his dialogue called the Phaedrus, and his character Socrates has this to say about good writing:

“But I think that you would assert this, at any rate: that every speech, just like an animal, must be put together to have a certain body of its own, so as to be neither headless or footless but to have middle parts and end parts, written suitably to each other and to the whole.”

To put Socrates’ words into our own words, we might say that a good piece of writing is extremely well ordered; each part is essential and is where it is because that is what is required for the writer to get their idea across. But, being well-ordered does not necessarily mean that it will be easy to understand! That order might be designed in such a way as to assist us in repeating the same thought that Plato had, but in such a way that it becomes our own. Plato generously guides us across the terrain, but the ascent is steep and not for the faint of heart.

Thus, when we find a puzzling passage in a great work of literature, we might be tempted to say to ourselves, “That does not make any sense. I guess people were not very good at writing back then.” I would propose an altogether different attitude or disposition toward perplexing passages. When we are confused, we ought to ask ourselves instead, “Why did the author place this passage here? How does this passage help advance other themes or questions that the book has been asking us to pursue?” Asking this kind of question is good at almost any point when we are reading. Why did Jane Austen show us one conversation in the room and not the other?

Here is a quote from Vladimir Nabokov’s “Good Readers, Good Writers,” that is broadly consistent with how we have approached thinking about reading so far:

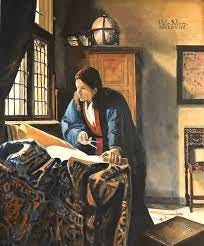

“Curiously enough, one cannot read a book: one can only reread it. A good reader, a major reader, an active and creative reader is a rereader. And I shall tell you why. When we read a book for the first time the very process of laboriously moving our eyes from left to right, line after line, page after page, this complicated physical work upon the book, the very process of learning in terms of space and time what the book is about, this stands between us and artistic appreciation. When we look at a painting we do not have to move our eyes in a special way even if, as in a book, the picture contains elements of depth and development. The element of time does not really enter in a first contact with a painting. In reading a book, we must have time to acquaint ourselves with it. We have no physical organ (as we have the eye in regard to a painting) that takes in the whole picture and then can enjoy its details. But at a second, or third, or fourth reading we do, in a sense, behave towards a book as we do towards a painting.”

Nabokov’s advice, in some sense, to read a book so often and so thoroughly, that you begin to see the book all once. When you read the beginning, you have the middle and the end in mind, and you begin to see the intricate relationship of each of the parts. Arthur Schopenhauer expresses the same thought in the preface to his The World as Will and Representation:

“It is self-evident that under these circumstances no other advice can be given as to how one may enter into the thought explained in this work than to read the book twice, and the first time with great patience, a patience which is only to be derived from the belief, voluntarily accorded, that the beginning presupposes the end almost as much as the end presupposes the beginning, and that all the earlier parts presuppose the later almost as much as the later presuppose the earlier.”

Thus, Schopenhauer insists that, if his book is to be properly understood, the reader must immediately read it a second time in order to understand the thought he wishes to impart.

I’ll offer one final example from Thoreau’s Walden:

“To read well, that is, to read true books in a true spirit, is a noble exercise, and one that will task the reader more than any exercise which the customs of the day esteem. It requires a training such as the athletes underwent, the steady intention almost of the whole life to this object. Books must be read as deliberately and as reservedly as they were written.”

Close reading, then, is not something you can become good at overnight. It requires a lot of practice—going to the gym for a couple of weeks is not enough to make you beautiful and powerful! In order to make your mind increasingly capable of unraveling carefully wrought rhetorical strategies from cautious writers, one must humbly sit before the great thinkers in addition to learning from other pupils of these thinkers who are farther along. Much of this practice will be wasted, however, if one fails to conceive of the activity in the way that Plato, Nabokov, Schopenhauer, and Thoreau propose.

Other essays on reading and writing:

This was a very nice post. Thank you for writing