Editor’s Note: I asked Dig Dug if he was interested in having a Classical Conversation because he posts many illuminating threads on classical scholarship on X. For prudent reasons, he has no interest in using his voice on the internet, but he generously offered to write an essay instead. This is an outstanding essay that covers a lot of ground in an accessible way; he perfectly balances clarity, insight, and erudition. He walks us through a fascinating subject: the birth of classical scholarship in the classical world. Please follow Passage Prize winning author Dig Dug on X.

By Dominated by Dig Dug

Introduction

Classical scholarship is the study of the history of ancient Greek and Roman literature. It involves collection, elucidation and, where necessary, emendation and restoration of texts. As a discipline, it began around 300 BC in the great libraries of the Hellenistic world. But since the beginning of Greek poetry with Hesiod and Homer, and the large amount of oral poetry which does not survive, poets were self-reflective and alluded to each other, an early form of scholarship.

The Beginnings and the Classical Period

The first three acts of scholarship known to us all involve Homer. Probably about 550 BC, the Athenian tyrant Peisistratus is said to have ‘assembled’ the ‘confused’ books of Homer. This comment comes from Cicero, but we have absolutely no idea what Peisistratus did to Homer’s poems. A generation later, two men began with interpretations of Homer. Xenophanes of Colophon was a rhapsode and made his living both reciting the poems of Homer and attacking him—the first act of literary criticism of which we know. Xenophanes blamed Homer for presenting the gods as engaged in shameful and unlawful things such as theft, adultery, and telling lies. Around the same time, Theagenes of Rhegium came to Homer’s defense. It is said that he gave allegorical interpretations of Homer, suggested corrections to the text, and was the first to write about Homer’s language. He also seems to have investigated Homer’s birthplace, family, and time frame. The Contest of Homer and Hesiod—a story about a competition between the two poets—probably first came into being around 500 BC.

The fifth century BC, the acme of Greek brilliance, saw continued interest in the poetry of the past. The Sophists, men such as Protagoras and Gorgias, were paid teachers who gave interpretations of epic and other old types of poetry. But their principal interest was not in the poetry itself, they were not ‘bookish.’ Their purpose was to take lessons from the past to educate their students, especially in matters of politics. The Sophists were also concerned with what we could call grammar or ‘correctness’ of speech. The end here, from the Sophists’ perspective, was eloquence in public speaking in order to win people to your view. Gorgias’ student and successor Alcidamas wrote a work entitled Mouseion (‘The Shrine of the Muses’) which contained a version of The Contest of Homer and Hesiod as well as anecdotal and biographical details about earlier authors.

The fifth century also saw the rise of more readily available texts. Written Greek goes back to the eighth century at least (not counting Linear B), but by the end of the fifth century, we hear about places in Athens where one could purchase ‘books’ (βιβλία)—in reality, papyrus scrolls. Passages in Aristophanes, Plato, and Xenophon all record cheap, easily and widely available books. It is hard to imagine the histories of Herodotus and Thucydides as anything but large books. We learn that copies of the plays of the great tragedians were available soon after the performance. In Aristophanes’ Frogs (405 BC), Dionysus recounts that he was reading Euripides’ Andromeda. Individuals built up large personal book collections, we might even say small libraries (though nothing like what was to come).

Plato and Aristotle dominated the fourth century. Plato’s Cratylus (402 E), for example, contains an amusing etymological investigation into Poseidon’s name: he plays around with substituting letters to achieve different meanings—but this is not yet grammar per se. Aristotle of course wrote works such as his Art of Poetry and Rhetoric which are sophisticated studies of these types of writing. Diogenes Laertius (5.22) preserves a list of Aristotle’s writings with tantalizing titles such as On Poets, Six Books of Homeric Problems, and Proverbs. We get a taste of his solutions to Homeric “problems” in the 25th chapter of his Poetics (1461a 15): “ζωρότερον δὲ κέραιε may mean not ‘mix the wine stronger’, as though for a drunkard, but ‘mix it quicker’.” Aristotle collected an enormous library that was passed down through his successors, eventually ending up in Rome. Both Plato and Aristotle founded their own schools where they attracted students from all over the Greek world: Plato’s Academy was founded in 368 BC and lasted, in some form or another, for nearly a millennium, and Aristotle’s Lyceum in 335 BC which also lasted many centuries.

Aristotle’s famous student, Alexander the Great, sets the stage for the next part of our story: the Hellenistic age of great libraries and scholars. But first, a little on their relationship. In 343 BC, Philip II of Macedon invited Aristotle to become tutor to his thirteen year old son, Alexander. Aristotle also taught Alexander’s companions, who would themselves go on to be kings. Various authors from antiquity tell us that Alexander slept with a dagger and a copy of the Iliad, a gift from Aristotle, under his pillow. Some of Aristotle’s other students were said to have accompanied Alexander on campaigns for biological research.

The Hellenistic World

After Alexander the Great’s death in 323 BC, the next period of Greek history we refer to as the Hellenistic World. It lasted until the death of Cleopatra in 30 BC, or, in other words, for about the same amount of time as archaic and Classical Greece. The Greek world changed radically. Gone were the independent city states of Athens and Sparta. Everything was subsumed into large empires ruled, at first, by the companions of Alexander.

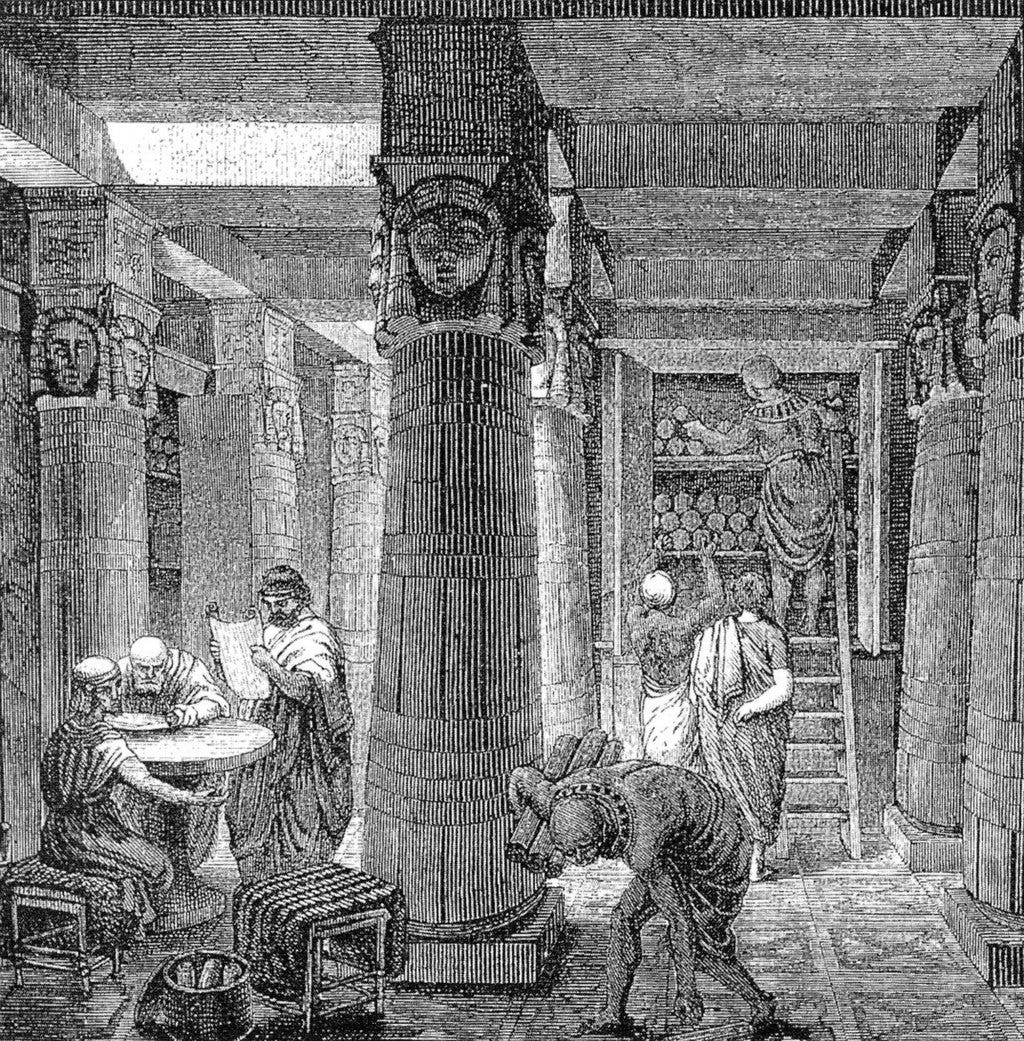

Our best information suggests that the concept of the great library in Alexandria came from Demetrius of Phalerum sometime after 297 BC. He had been a student of Theophrastus in Aristotle’s school and was known as an orator and for his extensive writings. The library itself was part of the so-called Museum, a gathering place for great minds in Alexandria. Poets and scientists were called to the Museum where they were given salaries, free meals, servants, etc. Although philosophy was not discouraged, the focus was on literary history, poetry, and science.

Ptolemy I, who founded the Museum, wanted to collect all the books known to man. How this happened has produced some amusing stories. According to one, every ship that docked in the harbor of Alexandria was searched for books, and if anything was found which did not already exist in the library, it was confiscated and a copy of it was given back to the owner. Another is that Ptolemy III desired the “official” copies of Aeschylus, Euripides, and Sophocles held at Athens, and put down a fifteen talent deposit to borrow them. He had copies of the plays made, and sent these copies back to Athens, keeping the originals and forfeiting his deposit.

It must be noted that the scholars in the Museum had rather catholic tastes and were interested in things outside of the Greek world. Early in the third century BC Manetho, an Egyptian priest, wrote a history of the pharaohs of Egypt in Greek, parts of which have survived. The poet-scholar Callimachus wrote a work entitled On Barbarian Customs. Then there is the so-called Letter of Aristeas. A very curious document, it records the translation in Alexandria during the reign of Ptolemy II Philadelphus (reigned 281-46 BC) of parts of the Hebrew Old Testament into Greek—the so-called Septuagint—by a team of 72 Jewish intellectuals over the span of 72 days. No one really believes this is what happened, however.

The Ptolemaic kings appointed a series of librarians, the first being Zenodotus of Ephesus. Among their roles, they were expected to oversee book collecting, produce original literary studies and works, and some might even be called upon to tutor the royal children. Zenodotus was said to be the first διορθωτής (diorthōtēs) or “one who straightens.” There has been much debate over what this word means, but it surely consisted of ordering books, cataloging them, classifying them, comparing divergent manuscripts and revising texts, and even writing stand-alone treatises explaining editorial decisions. There was certainly some combination of these things, and it likely meant different things to different people. We know that Zenodotus brought out “straightened” versions of Homer and Hesiod, and while we do not know much about them, certain traces are peculiar indeed. His copy of Homer looks to have started with a treatise on the number of days in the Iliad and a life of Homer.

We hear about the works of many scholars. Alexander of Aetolia edited the tragic poets, and Lycophron of Chalcis the comedians. The poet-scholar Callimachus was never elevated to librarian, but composed a 120 volume collection, the Pinakes, which was a detailed catalog of the library’s holdings, with authors’ biographies, nicknames, and lists of their work as well as other details. It was an unprecedented task. Librarians after Zenodotus include Apollonius of Rhodes (his epic poem the Argonautica survives), Eratosthenes of Cyrene, Aristophanes of Byzantium, and Aristarchus of Samothrace—considered to be the greatest of ancient literary scholars. Various scholars, then as now, engaged in literary disputes, for example Callimachus' criticism of the Peripatetic Praxiphanes in his Against Praxiphanes—sort of like literary reviews and bickering in the New York Times.

Literature was not all, however, being investigated in Alexandria. A few words about this. Eratosthenes was a poet-scientist, and made advances in chronology and geography. Archimedes spent time in Alexandria studying mechanics. Herophilus of Chalcedon and Erisistratus of uncertain birthplace made enormous advances in anatomy and medicine, presumably learning much from native Egyptians. They both engaged in dissections and even in vivisection. The Egyptians, of course, had been cutting into human bodies for thousands of years to make mummies, but in most of the Greek world, aside from Alexandria, corpses were inviolable.

Ptolemy VIII Physkon (‘fatso’), in his early days himself studying in the Museum and writing on Homer (we know of his suggested emendation in Odyssey 2.72 from ‘violet’ to ‘water-parsnip’), brought violence to Alexandria in 145 BC in a dynastic struggle which led to the dispersal of scholars across the Mediterranean world. The librarian Aristarchus had supported Physkon’s rival, and was forced to flee to Cyprus where he soon died. Others fled to Pergamum, where there was a center of learning second only to Alexandria, and to the islands.

After Alexandria’s Golden Age

As the flame of the Greek world flickered out, Rome was ascendant, and scholarship naturally took root there. In Rome we hear of scholars such as Tyrannion, Tryphon, Philoxenus, and Diocles—their main activities seem to have been writing commentaries on commentaries rather than assembling new critical editions. The Roman general Sulla had transferred Aristotle’s library from Athens to Rome in 84 BC, and there Tyrannion put it “in order.” Things had also cooled off politically in Alexandria and scholarship there took root again. One of the greatest scholars of the age was Didymus Chalcenterus (“bronze guts”) also called Bibliolathes (“book forgetter”). He is said to have written some four thousand treaties—so many, in fact, that he forgot what he had written, hence his second nickname. Much of our knowledge of the work of previous Alexandrians is preserved through him.

In the next few centuries, scholars’ focus was on explaining mythology, compiling dictionaries of all the words used by this or that earlier writer (Homer, of course, always being the most important), and producing grammars and focused studies of Greek language, such as work on etymology and grammar. Some of these writings have come down to us intact, such as Hephaestion’s book on Greek meter, and Apollonius Dyscolus’ works on Greek grammar. Also extant are Galen’s commentaries on Hippocrates and Porphyry’s works on Aristotle, Homer, Plato, and Ptolemy. This brings us down to about 275 AD.

Naturally much has been left out of this brief summary. Many names worthy of mention are missing. If you wish to learn more, I can recommend a few books. Pfeiffer’s History of Classical Scholarship: From the Beginnings to the End of the Hellenistic Age (Oxford, 1968) is breathtaking in its depth of knowledge. Reynolds’ and Wilson’s Scribes & Scholars: A Guide to the Transmission of Greek & Latin Literature (Oxford, 1991, 3rd ed.) is a classic. Finally, Dickey’s Ancient Greek Scholarship: A Guide to Finding, Reading, and Understanding Scholia, Commentaries, Lexica, and Grammatical Treatises, from Their Beginnings to the Byzantine Period (Oxford, 2007) is excellent, though technical, and one should know some Greek before approaching it.