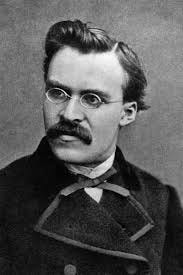

I received a question about to how to approach Nietzsche for the first time. I read a lot of Nietzsche many years ago, and I thought that I understood him at a deep level. I started re-reading him again recently and was astonished at how little I had understood previously.

But this is a good thing.

I'll make a suggestion on how to first approach Nietzsche and this approach would probably work with many other deep and sophisticated authors. This is very introductory, but it is good to get the basics right.

Take Beyond Good and Evil for example. I would first read it relatively quickly all the way through, maybe making some light annotations. You will not understand many important passages in the book but that is okay. You are going to have to read it again anyway.

Now you have an outline of the whole work in mind. The advantage to doing this first is that you can now think about the last words of the book while you read the beginning; you can start to think about how the book fits together as a whole. You are now no longer groping around in a completely dark room.

Now re-read BGE, but go much more slowly. Read the preface 4 or 5 times. Aristotle says that the beginning is half of the whole. Every great book that I've ever read will accomplish something extraordinary in the opening that needs to be understood for the rest of the book to really make sense.

Nietzsche gives helpful titles to his sections. The first one is called On the Prejudices of the Philosophers. You could make a list of each of the prejudices he mentions. You could ask: do these same prejudices apply to Nietzsche or has he gotten past them?

The same thing applies to the next section The Free Spirit. I know that it sounds ridiculously obvious, but you could do much worse than writing in a notebook what you think Nietzsche ultimately thinks a free spirit is. Does he always present it the same way or are there differences in his presentation? What task should the free spirit try to accomplish?

You can follow this pattern of writing over the course of the whole book. If you are able to provide even a provisional articulation of what Nietzsche thinks nobility is, what he thinks about the future of European politics, what our virtues are, what a religion is, and so on and so forth, you will understand him better than the majority of the people who invoke his name.

I'm stressing the need to focus on the obvious because when I was younger, a vice of my reading was to exclusively look for the secret teaching of the book or to have insanely close idiosyncratic readings of passages. I didn't want to be a midwit surface grazer--I didn't want the "ism". Instead, I was a in a cave beneath Plato's cave! But I think that making sure that you understand the surface, the basic argument being made, is an indispensable prerequisite for eventually grasping a more esoteric teaching if such a teaching is to be found.

It is important to note that Nietzsche writes in aphorisms. These are distillations of thought where Nietzsche transports you to the top of a mountain but he doesn't necessarily tell you how he got up there. One of the great virtues of this, is that the reader has to figure out how he got there, so that you can do so yourself in the future.

On the other hand, the aphoristic style tends to conceal the coherence of the book. At least on this reading, I see an argument unfolding in the first 9 aphorisms that is advanced in each about why philosophy has to be understood as psychology or physiology; that "truth" is the expression of the philosopher's physiological demands for the preservation of his own type and his attempt to seduce you into thinking his valuations ought to be yours. (I'll talk more about this in the space).

In other words, try to ask why does one aphorism come after the previous one? How are they connected? This is much harder to do in the Epigrams and Interludes section, but there might even be some unity in that section; or at the very least it serves as a kind of bridge between halves of the book.

Now you have completed a thoughtful and slow re-read. You might then see what Nietzsche says about Beyond Good and Evil in his book Ecce Homo where he has short sections discussing all of his published works. If you love the book, you'll keep coming back again and again. And then you'll learn German. And then you'll start the process over again in the original language. And if you don't love it, that's fine. You'll find another book that speaks to you. But you won't regret your time having dwelt with Nietzsche for 2 readings of BGE.

How would you propose beginning with Nietzsche?

Here is a tiny smattering of secondary sources you might find useful for studying Nietzsche’s Beyond Good and Evil after you have read it a few times (make other suggestions below):

Leo Strauss’s Course Lectures

Laurence Lampert’s Nietzsche’s Task

Maudemarie Clark / David Dudrick’s The Soul of Nietzsche’s Beyond Good and Evil

Thank you for this. Good advice and appreciated the analysis on the aphorisms!

Appreciate your advice about how to read great books, in general, and agree. Thank you.

Curious to get your thoughts on this question: in general, when is the most appropriate time to turn to secondary works? Before? As you go along? After the first read? Never?

For example, reading the Republic—how would you think about reading Bloom’s interpretive essay, or City and Man?