We made a small change to the format, breaking the reading into three parts and having discussions after each part. My interpretive notes are below. You should go check out William’s stack for his essay on the reading.

1) Lines 1 – 305 To take the horse or not to take the horse? Sinon’s deception and the sea-serpents.

Aeneas tells the Carthaginians about Troy’s final hours. In his prefatory remarks, Aeneas speaks of it as a tragedy in which he plays a leading role; to play a role in a tragedy (a play) is to speak lines written by someone else, which is to say, the description emphasizes the fated character of Aeneas’ life. However this may be, Aeneas embarks on his story, and in this way, takes on the role of Virgil, just as Odysseus took on the role of Homer in books 9 – 12 of the Odyssey.

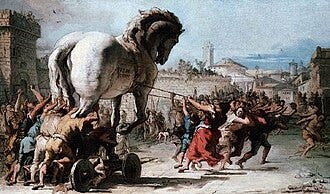

The Greeks have sailed away—though not too far away—and have left behind a massive wooden horse as a gift for Pallas Athena (not for the Trojans as is sometimes popularly assumed). The first Trojan to speak, Thymoetes, wants to take in the horse. The second, Capys, suspects a trap and even goes as far as to accurately describe precisely what the Greeks have in mind to do: hide men in the horse. He suggests that they destroy it. Laocoon, a priest of Neptune (mentioned in Book Three of the Iliad), lends his voice to those in opposition to taking the horse: “Whatever it is, I fear the Greeks, especially bearing gifts.” He throws a spear into the horse and it makes “echoing groans” which must mean that it is hollow and thus may contain enemy combatants.

(an interesting Virgilian omission from the Homeric account presented by Odysseus is Helen testing the resolve of the men inside by calling out to them as if their wives were calling)

Before further deliberation can take place, a young Greek named Sinon comes into view, ready with a treacherous story. Sinon establishes his trustworthiness as a speaker by emphasizing that the Greeks, and especially Ulysses, are his bitter enemy. His kinsman who opposed going to Troy was killed by Ulysses. Sinon wants revenge against the Greeks. Because of this, he says that if the Trojans were to kill him, they would be benefitting the Greeks, not themselves. Sinon further establishes his credibility by saying that Ulysses viciously tried to sacrifice him, to bring about a safe voyage home; however, he managed to get away at the last moment. This part of the speech also points to the Greeks being serious enough about leaving that they would sacrifice one of their own. Throughout his speech, he characterizes Ulysses as functionally in charge of the Greeks—not Agamemnon.

Priam frees Sinon who explains that the massive horse is to appease Pallas, who is angry at Ulysses for stealing her image out of a Trojan temple. Finally, Sinon relies on the pious character of the Trojans, telling them that the horse is sacred, and any violation of it would lead to disaster. And, this last statement is miraculously and spectacularly confirmed when serpents emerge and kill Laocoon and his children for Laocoon’s audacity to test the horse.

Virgil seems to present Fate as heavy-handed or immediately effectual. There is no leaving it up to chance whether or not the Trojans would be convinced by Sinon’s words; there isn’t a subtle goddess taking away the wits of the Trojans, but an overwhelming apparently divine intervention which admits of no ambiguity. Usually omens admit of ambiguity…think of Penelope’s dream. It had a kind of clear-ish meaning where one could plausibly read it as Odysseus coming home to kill the suitors, but a closer look reveals that Penelope might at least have mixed feelings (she is sad to see geese killed in the dream, etc).

Should the Trojans have admitted the horse? Even if they granted that the horse ought not to be disturbed in light of the serpents, wouldn’t prudence dictate that they send a vessel of some kind to investigate Tenedos? It would appear that their hopes for the cessation of the war and fear of the gods combined to blot out such prudential considerations from their minds.

2) Lines 305 – 727 The Greeks brutally destroy Troy, taking no prisoners.

It is incredible how effective Virgil’s presentation of the Greeks is at making me morally despise them. I was about to start this section with a sentence like, “That bastard Sinon opens the womb of the horse…” We are meant to see the Greeks as vicious, rapacious, predatory, and willing to lie about the gravest matters. Virgil really pushes us to see things from the Trojan point of reference; I don’t think in my reading of Homer that I ever felt this same kind of morally charged affect.

An interesting line that is related to this comes at 487 when Aeneas kills a few Greeks and dons part of their gear in order to deceive the Greeks: “Call it cunning or courage: who would ask in war?” If one were to apply this dictum equally to the Greeks…well, then it doesn’t make as much sense to moralize about how they approach the war. After all, Troy is an imperial city! (in the Iliad, we learn that the Greeks overcame 23 of their cities, and many foreigners come to assist the Trojans.) Strikingly, Aeneas is punished for doing this, as some Trojans wind up throwing spears at him. It almost like Aeneas is in this strange world where he is punished for being slightly immoral, while the Greeks are able to light the Trojan altars on fire without consequence.

At any rate, a war ravaged ghost of Hector appears to Aeneas in a dream and tells him to escape Troy. The battle cannot be won, but a new city can be founded. Hector is exceedingly clear; again, there is no room for misinterpretation. Nevertheless, Aeneas doesn’t act on Hector’s advice. Instead, he thinks to himself: “what a noble thing it is to die in arms.” His initial plan, then, is to kill as many Greeks as he can before he falls.

As an aside, it is remarkable that Aeneas’ piety never falters. Even as he says, “The gods who shored our empire up have left us, all have deserted their altars and their shrines” (440 – 441) he is also dead set on making sure that the hearth gods are well attended to (892 – 893).

The most disturbing episode in this section is when Achilles’ son Pyrrhus / Neoptolemus kills Priam’s fleeing son, Polites, right in front of him. Priam says that Achilles was much more honorable than his son. Pyrrhus replies that Priam can have the pleasure himself of reporting that message to Achilles in the underworld. Before this, Hecuba had tried to get Priam to go to the altar—presumably with the hope that the Greeks would respect the altar and not wish to pollute it. That hope makes it all the more impious or outrageous when Pyrrhus “drags the old man straight to the altar” and buries his sword deep in his flank. Subsequently the head is severed from the body. And this, after Priam impotently threw a spear at him. So we see the strong do what he wills and the weak suffer what he must. We’ll have to bear these scenes in mind when we see how the Trojans deal with subsequent enemies.

3) Lines 728 – 998 Venus steers Aeneas toward his family; all but Creusa escape

I found Venus’ speech to Aeneas to be perhaps the most striking part of the reading. Aeneas briefly considers punishing Helen for her role in the destruction of Troy. Venus turns her son’s attention to his family, whom Venus claims she has protected. She also tells Aeneas where all of the blame lies:

Think: it’s not that beauty, Helen, you should hate.

Not even Paris, the man that you should blame, no,

It’s the gods, the ruthless gods who are tearing down

The wealth of Troy, her toppling towers.

This is a kind of inversion of what Zeus says in Book One of the Odyssey, where he says that mortals often blame their misery on the gods rather than on their own foolishness. Here it is the gods alone who bear the blame. I wonder if Aeneas does not fully accept this; otherwise, he wouldn’t include such morally charged descriptions of the Greeks throughout his tale to the Carthaginians; and chronologically, he tells this tale after Venus tells him this.

(For an example of someone who really sees the world as fated to the maximum extent, see Melville’s Ishmael. He announces in the first chapter that the Fates are the stage managers of the world. In the final chapter, when Ahab finally tries to accomplish his aim of killing of the White Whale, Ishmael is one of the rowers on Ahab’s small vessel. Ishmael does not talk about his fear of death, or his concern when Ahab dies, or even of his clothes getting wet or the way the sea feels as he falls into the ocean. He seems to think that: what will be, will be. He is there as an observer of the slice of the cosmos which was given to him to perceive.)

We get another call back to Homer when Venus removes the mist from Aeneas’ eyes so that he can see that it is the gods who are destroying Troy and literally uprooting it from the earth. Athena had removed the mist from Diomedes’ eyes in Books Five and Six of the Iliad so that he could perceive who the gods were on the battlefield. The general or fundamental situation of human beings as such is that we do not see the world as it is or that we have mist before our eyes. It is a question whether we need a divine miracle to remove the mist or whether we can do this on our own. Virgil and Homer at the very least make us aware of the mist.

Finally, Venus tells Aeneas the same thing that Hector did: run! Aeneas does the first part of what Venus has in mind in going straight to Anchises. However, his father has no interest at all in leaving. He feels that, as an old man, he has already been a burden on the city for many years. He feels, not unreasonably, that this is the right time and way for him to die. Aeneas, for his part, holds it to be so shameful not to take his father with him that he returns to his original plan: dying with a sword in his hand. In this way, his father comes to light as more important to him than either Hector or Venus.

Aeneas’ wife cries out in anguish and another omen emerges: flame that does not burn emerges round the crown of their son Iulus’ / Ascanius’ head. They try to put it out before realizing that it might be a positive pointer toward his future rule over a people. Anchises demands more divine proof and says to Jove, “if our devotion has earned it, grant us another omen. Father, seal this first clear sign” (859 – 861). Jove sends thunder and a shooting star. Now that Hector, Venus, the flames, and the thunderous star have all appeared, Aeneas finally accepts that his lot is not to die with a sword in his hand in Troy.

He carries his father on his back while holding his son’s hand with Creusa right behind them…she doesn’t make it. After assuring that his father, son, and the household gods are safe, he runs back into the city in search of her, only to discover her ghost, who tells him of the good things he will accomplish. Aeneas tries to hug her just as Odysseus tried to hug his mother in the underworld. Manly tears gush down his cheeks.